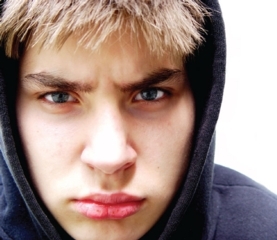

Mike S. (not his real name) was 13 years old when one of us (Lilienfeld) met him on an inpatient psychiatric ward, where Lilienfeld was a clinical psychology intern. Mike was articulate and charming, and he radiated warmth. Yet this initial impression belied a disturbing truth. For several years Mike had been in serious trouble at school for lying, cheating and assaulting classmates. He was verbally abusive toward his biological mother, who lived alone with him. Mike tortured and even killed cats and bragged about experiencing no guilt over these actions. He was finally brought to the hospital in the mid-1980s, after he was caught trying to con railroad workers into giving him dynamite, which he intended to use to blow up his school. According to psychiatry’s standard guidebook, theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (now in its fifth edition), Mike’s diagnosis was conduct disorder, a condition marked by a pattern of antisocial and perhaps criminal behavior emerging in childhood or adolescence.Psychologists have long struggled with how to treat adolescents with conduct disorder, or juvenile delinquency, as the condition is sometimes called when it comes to the attention of the courts. Given that the annual number of juvenile court cases is about 1.2 million, these efforts are of great societal importance. One set of approaches involves “getting tough” with delinquents by exposing them to strict discipline and attempting to shock them out of future crime. These efforts are popular, in part because they quench the public’s understandable thirst for law and order. Yet scientific studies indicate that these interventions are ineffective and can even backfire. Better ways to turn around troubled teens involve teaching them how to engage in positive behaviors rather than punishing them for negative ones.

Mike S. (not his real name) was 13 years old when one of us (Lilienfeld) met him on an inpatient psychiatric ward, where Lilienfeld was a clinical psychology intern. Mike was articulate and charming, and he radiated warmth. Yet this initial impression belied a disturbing truth. For several years Mike had been in serious trouble at school for lying, cheating and assaulting classmates. He was verbally abusive toward his biological mother, who lived alone with him. Mike tortured and even killed cats and bragged about experiencing no guilt over these actions. He was finally brought to the hospital in the mid-1980s, after he was caught trying to con railroad workers into giving him dynamite, which he intended to use to blow up his school. According to psychiatry’s standard guidebook, theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (now in its fifth edition), Mike’s diagnosis was conduct disorder, a condition marked by a pattern of antisocial and perhaps criminal behavior emerging in childhood or adolescence.Psychologists have long struggled with how to treat adolescents with conduct disorder, or juvenile delinquency, as the condition is sometimes called when it comes to the attention of the courts. Given that the annual number of juvenile court cases is about 1.2 million, these efforts are of great societal importance. One set of approaches involves “getting tough” with delinquents by exposing them to strict discipline and attempting to shock them out of future crime. These efforts are popular, in part because they quench the public’s understandable thirst for law and order. Yet scientific studies indicate that these interventions are ineffective and can even backfire. Better ways to turn around troubled teens involve teaching them how to engage in positive behaviors rather than punishing them for negative ones.

You’re in the Army Now

One get-tough technique is boot camp, or “shock incarceration,” a solution for troubled teens introduced in the 1980s……..