A new report from the Brennan Center for Justice concludes that “unnecessary incarceration” — imprisoning people for low-level offenses and keeping them there for years — is ruining hundreds of thousands of lives, wasting billions of dollars and having little effect on public safety.

A new report from the Brennan Center for Justice concludes that “unnecessary incarceration” — imprisoning people for low-level offenses and keeping them there for years — is ruining hundreds of thousands of lives, wasting billions of dollars and having little effect on public safety.

If you’ve been following the debate over mass incarceration in the United States, these arguments sound familiar. The U.S. is home to 5 percent of the world population but nearly a quarter of the world’s prisoners. Roughly 2.2 million Americans are behind bars, giving us the highest incarceration rate of nearly any country in the world.

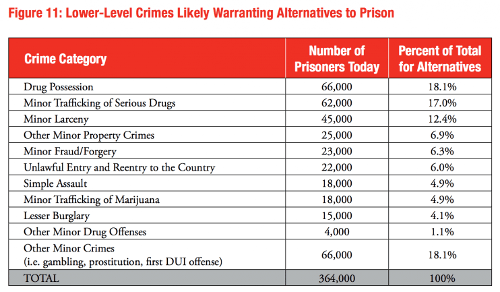

But the Brennan Center’s new report is noteworthy for quantifying exactly how many of our prisoners the authors believe shouldn’t be behind bars. Approximately 364,000 people are serving prison time for low-level offenses, like drug possession and minor burglaries. In recent years, more and more research has shown that prison terms are not particularly effective at deterring these crimes or rehabilitating the people who commit them. For these individuals, time behind bars may even increase their likelihood to commit more crime in the future.

As part of a three-year analysis of state and federal penal codes and prisoner data, the Brennan Center found that these low-level inmates make up roughly 25 percent of the current prison population. For these offenders, incarceration alternatives like probation, drug treatment or community service would be more effective, the report determined.

To arrive at this number, the report’s authors analyzed a number of factors that play into various offenses: the seriousness of the crime, whether the crime involved a victim (as in burglary) or not (as in drug use), the perpetrator’s state of mind (e.g., whether an offense was pre-meditated or spontaneous) and the risk of recidivism associated with the crime.

“These factors reflect a social science and popular consensus on why we incarcerate — to deliver punishment, promote public safety, and rehabilitate,” the authors explain.

They applied their analysis to more than 370 crime categories encompassing everything from petty theft to first-degree murder. Drawing on decades of criminal justice research, they designated certain types of crime as “lower-level” — that is, not meriting incarceration for an initial offense.

“Among these lower-level offenses were crimes that did not result in serious harm to a victim or substantial destruction of property, for which malicious intent may not have been present, and/or for which prison was not effective at reducing recidivism,” the authors explain.

The low-level offenses identified by the authors are in the table below, along with the number of offenders currently serving prison time. They include 66,000 people serving prison time for simple drug possession, 70,000 for minor theft and other property crimes, and tens of thousands serving time for other minor offenses like prostitution, gambling and first-time DUI.

The authors call their recommendations “conservative,” saying “when the circumstances are ambiguous, they err on the side of protecting public safety.”

The report also identified another way to reduce the prison population: Shorten the sentences of people serving time for some violent crimes. More and more research is showing that, for certain crimes, longer sentences don’t have a deterrent or rehabilitative effect for most offenders. For instance, one recent analysis of multiple studies found “fairly consistent evidence of specific deterrence for low sentence ranges, but not for longer ones.”

Given that most crime is committed by young people, there may be little societal benefit to keeping elderly prisoners behind bars.

Most troubling, multiple studies are now finding that the longer prison stays actually increase an inmate’s likelihood of reoffending upon release. Handing out lengthy prison sentences in the name of public safety may actually be making society less safe.

To that end, the Brennan Center researchers recommend reducing prison sentences by 25 percent for a number of serious crimes, including robbery, major drug trafficking and murder. That would reduce the typical murder sentence from 11.7 to 8.8 years, or the typical robbery prison term from 4.2 to 3.2 years.

That’s a more modest reduction than reforms advanced by a number of other groups, like the ACLU, which calls for reducing the national prison population by half. The Brennan authors argue that their more middle-of-the-road approach “ensures that sanctions for serious crimes involve significant prison time, are at levels that deter recidivism while protecting public safety, and achieve significant savings.”

Taken together, the two reforms — eliminating sentences for some crimes and shortening them for others — would reduce the incarcerated population by 39 percent, save taxpayers $18.1 billion annually and have a negligible impact on public safety, the authors concluded. That’s a big chunk of change, equivalent to hiring and training 270,000 new police officers, or 327,000 new teachers, they calculated.